Continual machine learning aims to design and develop computational sytems and algorithms that learn as humans do. For example, as humans we are usually good at retaining the information learned in the past, abstracting shareable knowledge from them, and using the knowledge to help future learning and problem solving. The rationale is that when faced with a new situation, we humans use our previous experiences and knowledge to help deal with and learn from the new situation. Our biological neural network is very good at learning and accumulating knowledge continuously in a lifelong manner. I argue that it is essential to incorporate this capability into an artificial intelligence (AI) system to make it versatile, holistic and truly “intelligent”.

Single-Task Learning

In traditional supervised machine

learning (ML) setups, we train deep neural network (DNN) models independently on

datasets consisting of the inputs and labels, \(\{\mathcal{X}_n,

\mathcal{Y}_n\}\), which I enumerate as tasks \(T_{1:nmax}\), where \(nmax\) is

the maximum number tasks the model is expected to learn from. This is the most

commonly used ML paradigm in practice. However, this leads to huge computational

loads and scalability issues because we need aggregate the old and new data each

time a new task needs to be learned. This is because knowledge is not retained

between tasks (ie. knowledge is not cumulative, and the model cannot learn by

leveraging past knowledge). Training such models in this setup requires a

extremely large number of training examples to allow the model to generalize to

all possible situations in real-world dynamic environments. I’m going to refer

to this as Machine Learning (ML) 1.0.

Example: Perception for Autonomous Vehicles

Data collected

through driving can often be huge given that the output of the various sensors

like cameras, lidar and radar as well as internal signals from CAN bus and other

measurement units can easily be of the order of hundreds of megabytes per

second. The observations are also not equally informative.

It is difficult to come up with either a one-time dataset or modeling that can

cover all possible driving situations that an autonomous vehicle may encounter.

Driving rules, traffic behavior and weather conditions change from one place to

another and over time. So, it will be necessary to continuously collect such new

instances as they are encountered in order for the existing systems to adapt

accordingly. Thus, there is a need for the perception modules to learn

continuously and reliably from new data in a scalable manner but without

compromising on the knowledge obtained from previous training.

Continual Learning

In continual learning, a DNN learns the

tasks \(T_{1:nmax}\) in a sequential manner, and when faced with the \(n^{th}\)

task it uses the relevant knowledge gained in the past \(n-1\) tasks to help

learning for the \(n^{th}\) task. This suggests that a DNN should generate some

prior knowledge from the past observed tasks to help future task learning

without even observing any information from future task \(T_{n+1}\). Ideally, in

the continual learning setup we aim for \(nmax = \infty\). As we can see, this

is different from the traditional ML training setup because the prior knowledge

may be generated from the \(n-1\) tasks with or without considering the

\(n^{th}\) task’s data. That way, the learning becomes truly lifelong and

autonomous. It is also important to note that we are not jointly optimizing all

new and past tasks, but only the task we are currently training on. Now, I’ll

refer to this as ML 2.0.

Catastrophic Forgetting at a Glance

Continual learning

sounds awesome but if we ask ourselves why hasn’t there been much success with

this learning paradigm, it is due to a well-known problem in DNNs called

catastrophic forgetting or catastrophic interference [2, 3].

Catastrophic forgetting poses a grand challenge for DNNs, something that

was discovered a long time ago in the 90’s. In artificial neural networks,

everytime new information is learned, it forgets a little of what it had already

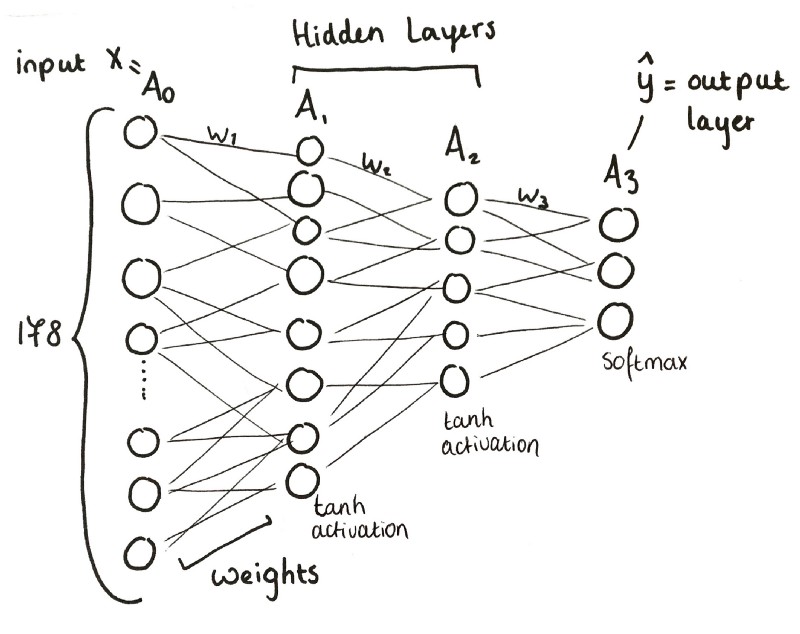

been trained on before. Neural networks store information by setting the values

of weights, which are the strengths of the synaptic connections between neurons

(see diagram below). These weights are also analgous to the axons in our brain,

the long tendrils that connect from one neuron to dendrites of another neuron,

and meet at microscopic gaps called synapses. Therefore, the value of the weight

between two neurons in an artificial neural network is roughly like the number

of axons between neurons in the biological neural network. When we train neural

networks, we try to minimize the loss function using some gradient descent

optimizer and backpropagation [1]. As a result, the weights are slowly adjusted when

we train the neural network iteratively on mini-batches of data until we achieve

the desired output or best test performance.

Now, what happens when we take this same model and train on new data that

we may have collected a few months later? The instant we start optimizing the

model again with gradient descent and backpropagation, we start overwriting the

pre-trained weights with new values that no longer represent the values we had

for the previous dataset. The network starts “forgetting”.

My Take on Continual Learning

Although, current research in

continual lifelong learning is still in its infancy, there have been several

promising research directions within the machine learning (ML) community [4]. I

strongly believe that within the next decade, DNNs will be capable of learning

continually to perform multiple tasks without any human intervention. This will

further enhance existing technologies that leverage AI such as perception for

self-driving cars, fraud detection, recommender systems, climate monitoring,

sentiment analysis, face recognition, and etc. It will also be crucial step

towards achieving artificial general intelligence (AGI), a long standing

challenge for many AI researchers.

References

[1] Chauvin, Y. and Rumelhart, D. E. (eds.). Backpropagation: Theory, Architectures, and Applications, ISBN 0-8058- 1259-8, 1995.

[2] French, R. Catastrophic forgetting in connectionist networks. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 3(4):128–135, 1999.

[3] McCloskey, M. and Cohen, N. J. Catastrophic interference in connectionist networks: The sequential learning problem. The Psychology of Learning and Motivation, 24: 104–169, 1989.

[4] Parisi, G. I., Kemker R., Part J. L., Kanan C., and Wermter S. Continual Lifelong Learning with

Neural Networks: A Review. Corr, abs/1802.07569, 2018.